Translate this page to any language by choosing a language in the box below.

Earth: Tectonic Plates

Earth: Tectonic PlatesThe earth is composed of three main layers:

But the core has 2 distinctly different regions: the inner core and the outer core. The ground beneath beneath you may feel hard, and it is for many miles, but not so many as you think. The earth's crust is just a thin, thin layer. Far thinner in proportion than the frosting on a cake. Beneath the crust is molten magma. That's right, the lava that comes out of volcanoes. And that makes up 70% of the volume of the Earth. All of humankind exists on the 30% of the Earth's surface that is the hard cooled magma. Or land as we know it. The remaining 70% or so is covered by water.

This land is actually floating on top of liquid magma. As the convection currents inside the earth cause the magma to move, so do the tectonic plates. North America is still moving farther away from Europe as new magma comes up in the Mid-Atlantic Rift. But the West Coast of North America is moving closer to Asia.

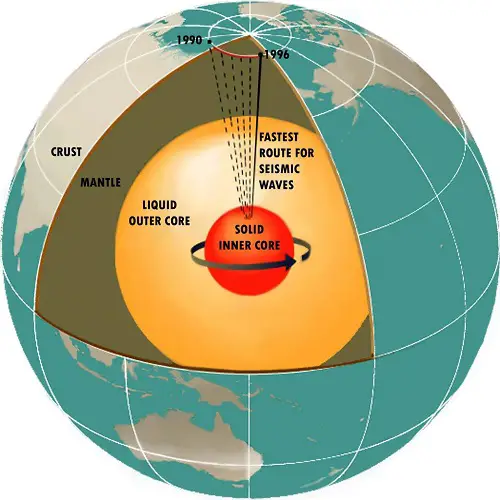

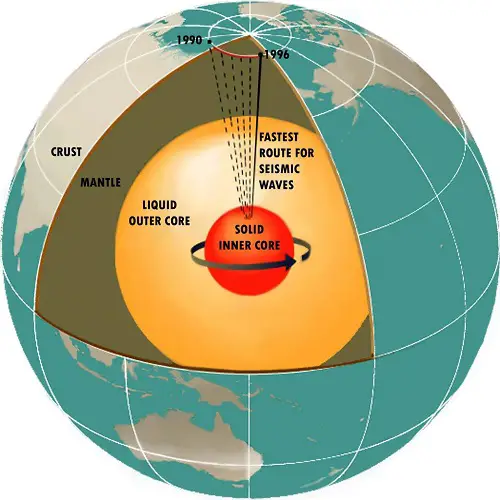

The diagrams at right and below show a schematic of the layers inside the earth.

Earth's crust is less than 60 miles (100 km) thick. Considering that it is about 4,000 miles to the center of the earth, 60 miles isn't much! The earth's crust is made up of about twelve plates, combinations of continents and ocean basins, which move around on the Earth's surface. The crust is much thinner under the oceans than under continents (see figure above).

The mantle is a dense, hot layer of semi-solid rock (a.k.a, lava when it surfaces) approximately 2,900 km thick. The mantle, which contains more

iron, magnesium, and calcium than the crust, is hotter and denser because temperature and pressure inside the Earth increase with depth. Not surprisingly, the Earth's internal structure influences plate tectonics. The upper part of the

mantle is cooler and more rigid than the deep mantle; in many ways, it behaves like the overlying crust. Together they form a rigid layer of rock

called the lithosphere (from lithos, Greek for stone). The lithosphere tends to be thinnest under the oceans and in volcanically active continental

areas, such as the Western United States. Averaging at least 80 km in thickness over much of the Earth, the lithosphere has been broken up into the

moving plates that contain the world's continents and oceans. Scientists believe that below the lithosphere is a relatively narrow, mobile zone in

the mantle called the asthenosphere (from asthenes, Greek for weak). This zone is composed of hot, semi-solid material, which can soften and flow

after being subjected to high temperature and pressure over geologic time. The rigid lithosphere is thought to "float" or move about on the slowly

flowing asthenosphere.

A tectonic plate (also called lithospheric plate) is a massive slab of solid rock, floating on the molten mantle. The plate sizes can vary greatly, from a few hundred to thousands of kilometers across; the Pacific and Antarctic Plates are among

the largest. Plate thickness also varies greatly, ranging from less than 15 km for young oceanic lithosphere to about 200 km or more for ancient

continental lithosphere (for example, the interior parts of North and South America).

Continental crust is composed of granitic rocks which are made up of

relatively lightweight minerals such as quartz and feldspar. By contrast, oceanic crust is composed of basaltic rocks, which are much denser and

heavier. The variations in plate thickness are nature's way of partly compensating for the imbalance in the weight and density of the two types of

crust. Because continental rocks are much lighter, the crust under the continents is much thicker (as much as 100 km) whereas the crust under the

oceans is generally only about 5 km thick. Like icebergs, only the tips of which are visible above water, continents have deep "roots" to support

their elevations.

Most of the boundaries between individual plates cannot be seen, because they are hidden beneath the oceans. Yet oceanic

plate boundaries can be mapped accurately from outer space by measurements from GEOSAT satellites. Earthquake and volcanic activity is concentrated

near these boundaries. Tectonic plates probably developed very early in the Earth's 4.6-billion-year history, and they have been drifting about on

the surface ever since-like slow-moving bumper cars repeatedly clustering together and then separating.

The edges of the plates are marked by concentrations of earthquakes and volcanoes. Collisions of plates can produce mountains like the Himalayas,

the tallest range in the world. The plates include the crust and part of the upper mantle, and they move over a hot, yielding upper mantle zone at

very slow rates of a few centimeters per year, slower than the rate at which fingernails grow.

Like many features on the Earth's

surface, plates change over time. Those composed partly or entirely of oceanic lithosphere can sink under another plate, usually a lighter, mostly

continental plate, and eventually disappear completely. This process is happening now off the coast of Oregon and Washington. The small Juan de Fuca

Plate, a remnant of the formerly much larger oceanic Farallon Plate, will someday be entirely consumed as it continues to sink beneath the North

American Plate.

Not surprisingly, the Earth's internal structure influences plate tectonics. The upper part of the

mantle is cooler and more rigid than the deep mantle; in many ways, it behaves like the overlying crust. Together they form a rigid layer of rock

called the lithosphere (from lithos, Greek for stone). The lithosphere tends to be thinnest under the oceans and in volcanically active continental

areas, such as the Western United States. Averaging at least 80 km in thickness over much of the Earth, the lithosphere has been broken up into the

moving plates that contain the world's continents and oceans. Scientists believe that below the lithosphere is a relatively narrow, mobile zone in

the mantle called the asthenosphere (from asthenes, Greek for weak). This zone is composed of hot, semi-solid material, which can soften and flow

after being subjected to high temperature and pressure over geologic time. The rigid lithosphere is thought to "float" or move about on the slowly

flowing asthenosphere.

The boundary between the crust and mantle is called

the Mohorovicic discontinuity (or Moho); it is named in honor of the man who discovered it, the Croatian scientist Andrija Mohorovicic. No one has

ever seen this boundary, but it can be detected by a sharp increase downward in the speed of earthquake waves there. The explanation for the

increase at the Moho is presumed to be a change in rock types. Drill holes to penetrate the Moho have been proposed, and a Soviet hole on the Kola

Peninsula has been drilled to a depth of 12 kilometers, but drilling expense increases enormously with depth, and Moho penetration is not likely

very soon.

Scientists have studied the upper mantle, including the tectonic plates, from analyses of earthquake waves (see figure for paths); heat flow, magnetic, and gravity studies; and laboratory experiments on rocks and minerals. Between 100 and 200 kilometers below the Earth's surface, the temperature of the rock is near the melting point; molten rock erupted by some volcanoes originates in this region of the mantle. This zone of extremely yielding rock has a slightly lower velocity of earthquake waves and is presumed to be the layer on which the tectonic plates ride. Below this low-velocity zone is a transition zone in the upper mantle; it contains two discontinuities caused by changes from less dense to more dense minerals. The chemical composition and crystal forms of these minerals have been identified by laboratory experiments at high pressure and temperature. The lower mantle, below the transition zone, is made up of relatively simple iron and magnesium silicate minerals, which change gradually with depth to very dense forms. Going from mantle to core, there is a marked decrease (about 30 percent) in earthquake wave velocity and a marked increase (about 30 percent) in density.

See the drawing at right, Cross section of the Earth, showing the complexity of paths of earthquake waves. The paths curve because the different rock types found at different depths change the

speed at which the waves travel. Solid lines marked P are compressional waves; dashed lines marked S are shear waves. S waves do not travel through

the core but may be converted to compressional waves (marked K) on entering the core (PKP, SKS). Waves may be reflected at the surface (PP, PPP,

SS).

The core was the first internal structural element to be identified. It was discovered in 1906 by R.D. Oldham, from his study of

earthquake records, and it helped to explain Newton's calculation of the Earth's density. The outer core is presumed to be liquid because it does

not transmit shear (S) waves and because the velocity of compressional (P) waves that pass through it is sharply reduced. The inner core is

considered to be solid because of the behavior of P and S waves passing through it.

Cross section of the whole Earth, showing the complexity of

paths of earthquake waves. The paths curve because the different rock types found at different depths change the speed at which the waves travel.

Solid lines marked P are compressional waves; dashed lines marked S are shear waves. S waves do not travel through the core but may be converted to

compressional waves (marked K) on entering the core (PKP, SKS). Waves may be reflected at the surface (PP, PPP, SS).

Data from earthquake

waves, rotations and inertia of the whole Earth, magnetic-field dynamo theory, and laboratory experiments on melting and alloying of iron all

contribute to the identification of the composition of the inner and outer core. The core is presumed to be composed principally of iron, with about

10 percent alloy of oxygen or sulfur or nickel, or perhaps some combination of these three elements.

Cross section of the whole Earth, showing the complexity of

paths of earthquake waves. The paths curve because the different rock types found at different depths change the speed at which the waves travel.

Solid lines marked P are compressional waves; dashed lines marked S are shear waves. S waves do not travel through the core but may be converted to

compressional waves (marked K) on entering the core (PKP, SKS). Waves may be reflected at the surface (PP, PPP, SS).

Many references are included by embedded links to the sources in the text above. Below are others:

Ways to save money AND help the environment:

Eat healthier AND save money: Instant Pot Duo Crisp 11-in-1 Air Fryer and Electric Pressure Cooker Combo with Multicooker Lids that Fries, Steams, Slow Cooks, Sautés, Dehydrates

Save water AND money with this showerhead adapter, it lets the water flow until the water is hot, then shuts off water flow until you restart it, ShowerStart TSV Hot Water Standby Adapter

Protect your health with these:

Mattress Dust mite-Bedbug protector, 100% Waterproof, Hypoallergenic, Zippered

Handheld Allergen Vacuum Cleaner with UV Sanitizing and Heating for Allergies and Pet, Kills Mite, Virus, Molds, True HEPA with Powerful Suction removes Hair, Dander, Pollen, Dust,

Immune Support Supplement with Quercetin, Vitamin C, Zinc, Vitamin D3

GermGuardian Air Purifier with UV-C Light and HEPA 13 Filter, Removes 99.97% of Pollutants

5 Stage Air Purifier, Features Ultraviolet Light (UVC), H13 True Hepa, Carbon, PCO, Smart Wifi, Auto Mode, Quiet, Removes 99.97% of Particles, Smoke, Mold, Pet Dander, Dust, Odors

Interesting Reads:

THE PREPPER'S CANNING & PRESERVING BIBLE: [13 in 1] Your Path to Food Self-Sufficiency. Canning, Dehydrating, Fermenting, Pickling & More, Plus The Food Preservation Calendar for a Sustainable Pantry

The Backyard Homestead: Produce all the food you need on just a quarter acre! Paperback

The Citizens' Guide to Geologic Hazards: A Guide to Understanding Geologic Hazards Including Asbestos, Radon, Swelling Soils, Earthquakes, Volcanoes

The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming

Book: The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History Paperback